The release of the Segment Anything Model (SAM) changed introduced a model that could cut out any object you clicked on. SAM-2 extended this capability to video. Now, SAM-3 has arrived, and it introduces a fundamental shift in how we interact with images and video.

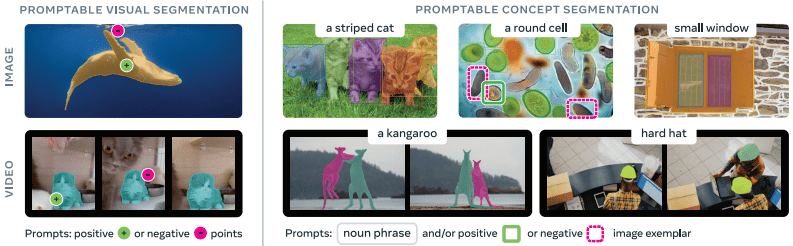

Previous versions relied on Promptable Visual Segmentation (PVS). This meant you gave the model a point or a box, and it gave you that specific object. SAM-3 introduces Promptable Concept Segmentation (PCS). Instead of asking for “this object,” you can now ask for “all instances of this concept.” Whether you type “striped cat” or draw a box around one car to find every car in a video, SAM-3 handles detection, segmentation, and tracking simultaneously.

In this blog post you will learn about:

- The Unified Architecture of SAM-3

- The Data Engine designed for open-vocabulary prompts.

- Performance & Video Tracking script using OpenCV and Python

From Visual Prompts (PVS) to Concept Prompts (PCS)

To appreciate the leap SAM-3 represents, we must first distinguish between the geometric task of previous models and the semantic task of the new architecture. The paper formalizes this as the transition from Promptable Visual Segmentation (PVS) to Promptable Concept Segmentation (PCS).

The Limitation of PVS (SAM-1 & SAM-2)

To understand why SAM-3 is such a significant architectural leap, we must first look at the constraints of its predecessors, SAM and SAM-2. In a PVS workflow, the user provides a spatial hint essentially telling the model “segment the object located right here” via a point, a box, or a coarse mask. The model’s objective is to resolve the boundaries of that specific target based on texture and edge information, without necessarily understanding what the object is.

Because PVS is strictly local, the model remains agnostic to the broader concept of the object. For example, if a user clicks on a single car in a crowded parking lot, a PVS model will return a perfect mask for that specific car, but it will completely ignore the dozens of other cars surrounding it. This limitation makes PVS excellent for precision editing of single assets but highly inefficient for tasks that require cataloging or analyzing entire scenes.

SAM-2 achieves tracking by following the specific pixels identified in the first frame as they move through time. If a new instance of the same object class enters the video later, for example, a second car driving into the frame at the ten-second mark, the PVS model will not automatically segment it because it was never explicitly prompted to do so. The user acts as the detector, manually finding and clicking every relevant object, while the model acts only as the segmenter.

Generalizing the Prompt Space: Text and Exemplars

A key innovation in SAM-3 is how it generalizes the concept prompt beyond just text. While simple noun phrases are the primary input, the authors recognize that language can be ambiguous or insufficient for describing specific visual targets. To address this, SAM-3 supports image exemplars as prompts.

A user can draw a box around a specific object (e.g., a rare machine part that is hard to name) and the model extracts the visual embedding of that object to use as a search query. This allows the model to find all other objects in the image or video that look semantically similar to the exemplar. This multimodal prompting system allows for a highly interactive “hybrid” workflow.

The paper describes a scenario where a text prompt alone might be too broad or too narrow. Users can refine their results by providing a text prompt (e.g., “helmet”) and then adding negative visual exemplars (boxes around “bicycle helmets”) to force the model to focus only on construction hard hats.

Handling Ambiguity and Temporal Continuity

The move to concept-based segmentation introduces complexities regarding ambiguity that did not exist in the geometric world of PVS. A text prompt like “mouse” could refer to a rodent or a computer peripheral. The paper details how SAM-3 includes an ambiguity handling module, often predicting multiple valid masks for a prompt and relying on the user to disambiguate through interactive refinement.

In the video domain, PCS introduces an approach to tracking known as “masklets.” Unlike PVS, which tracks specific pixels, PCS must maintain the identity of a concept across time even as new instances appear and disappear. If a user prompts for “dogs” in a video, SAM-3 must initialize a track for every dog present in the first frame, but also continuously run its detector to catch new dogs entering the scene in subsequent frames. This requires a dual-architecture approach where a memory-based tracker preserves the identity of existing objects (“Dog A”), while the detector scans for new ones (“Dog B”).

Finally, the paper outlines distinct strategies for resolving conflicts between detection and tracking. In crowded scenes or during occlusions, the detector might momentarily lose an object, or the tracker might drift. SAM-3 employs a mechanism called periodic re-prompting, where the high-confidence outputs of the detector are used to reset and correct the tracker. This ensures that the concept definition remains stable throughout the video, preventing the model from confusing similar-looking objects or losing track of an object that temporarily walks behind an obstacle.

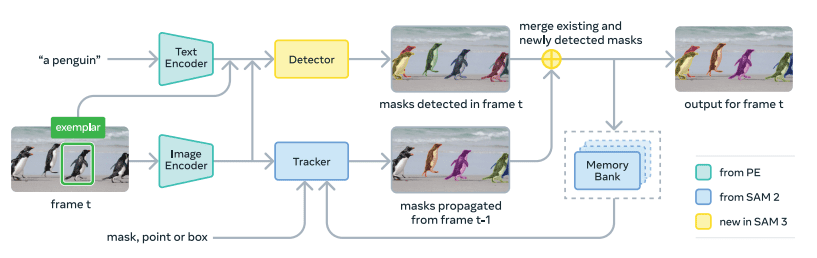

SAM-3 Architecture Overview

The Shared Backbone (Perception Encoder)

At the foundation of SAM-3 lies a unified vision backbone known as the Perception Encoder (PE). Unlike systems that might use separate networks for understanding text and processing images, SAM-3 utilizes a dual encoder design where the image and text encoders are aligned from the very beginning. The authors used a transformer architecture that processes the image into a set of feature embeddings.

The paper also describes a streaming approach where the Perception Encoder processes each incoming video frame only once. These computed features, referred to as unconditioned tokens serve as the single source of truth for the entire system. Once extracted, these features branch off to feed two distinct downstream components: the image-level detector and the video tracker.

This streaming design prevents redundant computation; the system does not need to re-encode the image when switching between detecting new objects and tracking existing ones. The backbone uses windowed attention, dividing the image into non-overlapping windows to manage computational costs, while applying global attention in specific layers to capture long-range dependencies.

The Image-Level Detector

The detector in SAM-3 is built upon the DETR (Detection Transformer) paradigm, specifically adapted to handle the requirements of concept segmentation. Its primary architecture consists of a Fusion Encoder and a Transformer Decoder.

The process begins with the Fusion Encoder, which acts as a bridge between the visual world and the user’s prompt. It takes the unconditioned image features from the backbone and conditions them by cross-attending to the prompt tokens. These prompt tokens can be derived from text (e.g., “blue boat”) or from visual exemplars (e.g., an embedding of a specific object cropped from the image). This fusion step effectively highlights the regions of the image that match the concept while suppressing irrelevant background noise.

Once the features are conditioned, they are passed to the Decoder. This component uses a set of learned object queries that scour the image features to localize potential matches. Unlike traditional detectors that are limited to a fixed list of categories, SAM-3 detector is open-vocabulary. It predicts a binary classification logit for each query, indicating whether that specific region corresponds to the prompt. Simultaneously, it predicts bounding box coordinates and segmentation masks.

The paper notes that this detector uses “Divide-And-Conquer” (DAC) strategies and iterative box refinement to achieve high precision, ensuring that the detected boundaries are pixel-perfect. Crucially, the detector is identity-agnostic.

This stateless design allows the detector to be extremely robust at recovering objects that were previously occluded. If an object disappears behind a wall and reappears, the detector will immediately spot it again, providing a fresh detection that the tracker can then use to re-establish the object’s history.

The Video Tracker

The video tracker in SAM-3 inherits the architecture of SAM-2, designed specifically to solve the temporal consistency problem that the detector ignores. The tracker operates on a memory-based mechanism. It maintains a memory bank that stores feature representations of objects from previous frames, as well as the initial frame where the user provided a prompt.

By referencing this history, the tracker can predict the motion and deformation of an object, generating a masklet which is a spatio-temporal tube that defines the object’s existence across time. The tracker’s role is to be identity-aware. While the detector finds all dogs, the tracker focuses on maintaining the specific identity of “Dog A” versus “Dog B.”

Tracker achieves identity-aware quality by propagating masks from frame t-1 to frame t. The architecture uses a memory encoder to compress the information from past frames and a memory attention module to condition the current frame’s processing on that historical context. This allows the model to handle complex scenarios, such as an object rotating or changing its appearance as it moves through light and shadow.

However, purely memory-based tracking can suffer from drift, when errors accumulate over time, or fail completely during long occlusions. To mitigate this, SAM-3 uses a “match and update” process. On every frame, the system compares the tracker’s predicted position for “Dog A” with the detector’s fresh findings. If they overlap significantly, the tracker’s memory is updated with the high-quality detection mask.

The Presence Head (Key Innovation)

One of the most significant architectural innovations in SAM-3 is the introduction of the Presence Head, which decouples the task of recognition (is the concept here?) from localization (where is it?). In standard DETR-like architectures, every object query tries to guess both what it is looking at and where it is. This often leads to phantom detections, where the model forces a prediction on background noise because it lacks a global understanding of the image.

The Presence Head solves the above mentioned problem by introducing a learned global token that attends to the entire image context before any specific object is localized. This global token is trained to answer a binary question: “Is the concept described by the prompt present in this image?” The output is a single scalar score between 0 and 1. The final confidence score for any individual object is calculated as the product of this global presence score and the local object score.

For example, if the model is prompted for “unicorn” and the Presence Head calculates a score of 0.01 (highly unlikely), this low score is multiplied against all object queries, effectively suppressing false positives across the board. The paper highlights that this mechanism significantly improves the model’s calibration, particularly on the new “IL_MCC” (Image-Level Matthews Correlation Coefficient) metric.

By separating the global semantic check from the local geometric check, SAM-3 avoids the common pitfall of open-vocabulary models: hallucinating objects in complex textures. This feature makes the model highly reliable for downstream applications like counting or filtering, where knowing that an object is not present is just as important as finding it when it is.

SAM-3: Video Tracking using OpenCV and Python

While the architecture of SAM-3 might be complex, implementing it for video inference is surprisingly straightforward. By combining SAM-3’s processor with standard libraries like OpenCV and PyTorch, developers can build a concept tracking pipeline that processes video streams frame-by-frame.

The provided code demonstrates a practical implementation where the model treats every frame as a new query. Because SAM-3’s detector is so robust, running the image-level model on every frame effectively results in stable tracking without needing complex state management for simple use cases.

Installation

Prerequisites

- Python 3.12 or higher

- PyTorch 2.7 or higher

- CUDA-compatible GPU with CUDA 12.6 or higher

Create a new Conda environment

conda create -n sam3 python=3.12

conda deactivate

conda activate sam3

Clone the repository and install the package

git clone https://github.com/facebookresearch/sam3.git

cd sam3

pip install -e .

Additional Dependencies

pip install -e ".[notebooks]"

pip install -e ".[train,dev]"

pip install einops

pip install opencv-python

pip install pycocotools

pip install scikit-learn

pip install scikit-image

Getting Started

Note from the Official Repository: Before using SAM 3, please request access to the checkpoints on the SAM 3 Hugging Face repo. Once accepted, you need to be authenticated to download the checkpoints. You can do this by running the following steps (e.g. hf auth login after generating an access token.)

The workflow begins by initializing the Sam3Processor. This wrapper handles the heavy lifting of image preprocessing and prompt encoding. We load the model onto the GPU and prepare it to accept incoming frames.

import cv2

import torch

import numpy as np

from PIL import Image

from sam3.sam3.model_builder import build_sam3_image_model

from sam3.sam3.model.sam3_image_processor import Sam3Processor

# Initialize the model and processor

model = build_sam3_image_model()

processor = Sam3Processor(model)

Inference Loop

The core logic resides in a standard OpenCV while loop. The script reads a frame, converts it from OpenCV’s default BGR format to RGB, and creates a PIL image.

Crucially, the prompt is defined as a comma-separated string of concepts, such as: “man’s hand, woman purse, Monkeys, Penguins, Humans…“. This demonstrates SAM-3’s ability to hunt for multiple distinct concepts simultaneously within a single pass of the model.

cap = cv2.VideoCapture("video2.mp4")

TEXT_PROMPT = "people dancing"

while True:

ret, frame_bgr = cap.read()

if not ret: break

frame_rgb = cv2.cvtColor(frame_bgr, cv2.COLOR_BGR2RGB)

pil_img = Image.fromarray(frame_rgb)

state = processor.set_image(pil_img)

#Query the image with the concept text

output = processor.set_text_prompt(state=state, prompt=TEXT_PROMPT)

# Output contains binary masks for all found concepts

masks = output["masks"]

Soft Visualization for Visually Clear Output

Raw segmentation masks are binary (0 or 1), which can look jagged when overlaid on video. Our implementation uses a custom visualization technique to create soft masks that blend aesthetically with the original video without occluding the original object.

Instead of a hard overlay, this code applies a Gaussian Blur to the mask edges before blending. This creates a glowing, semi-transparent effect (alpha=0.45) that highlights the object without obscuring the underlying texture details.

def visualize_mask_soft(frame_bgr, masks, color=(0, 255, 0), alpha=0.45, blur_k=21):

#Combine: All instance masks in One

combined = np.zeros(frame_bgr.shape[:2], dtype=np.float32)

for mask in masks:

m = mask.detach().cpu().numpy().squeeze()

combined = np.maximum(combined, m)

combined_blur = cv2.GaussianBlur(combined, (blur_k, blur_k), 0)

output = frame_bgr * (1 - alpha) + overlay_color * alpha

return output.astype(np.uint8)

Result

The Data Engine and SA-Co Benchmark

A deep learning model is only as capable as the data it observes during training. The authors of SAM-3 recognized that existing open-vocabulary datasets were insufficient for the new task of Promptable Concept Segmentation (PCS). To solve this, they engineered a massive, scalable pipeline called the SA-Co data engine. This engine operated in four distinct phases, progressively automating the labor-intensive parts of annotation to achieve a scale that would be impossible with humans alone.

Phase 1: Human Verification

The engine began by establishing a baseline using human annotators. In this initial phase, the system randomly samples images and generates candidate masks using early versions of the model prompted by simple captions.

Human verifiers were tasked with two critical checks: “Mask Verification” (is this mask accurate?) and “Exhaustivity Verification” (did the model find every instance of the concept?). If a prompt was marked as non-exhaustive, annotators manually added the missing masks.

This phase created the high-quality seed data necessary to train the subsequent AI verifiers, ensuring that the automated components of the pipeline were grounded in human-level judgment.

Phase 2: AI Verifiers

To scale up, the team introduced AI Verifiers, fine-tuned Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) like LLaMA 3. These models were trained to replicate the human verification tasks rating mask quality and checking for missing objects.

By offloading these routine checks to AI, the throughput of the data engine doubled. Human effort was then redirected solely to the most challenging cases, i.e, fixing specific errors identified by the AI or handling ambiguous concepts. This phase also introduced hard negatives by using an AI to propose adversarial noun phrases (e.g., asking for a “wolf” in an image of a “dog”) to force the model to learn precise semantic boundaries.

Phase 3 & 4: Domain Expansion and Video Extension

The final phases focused on diversity and temporal consistency. Phase 3 expanded the visual domains beyond standard web images to include specialized datasets (e.g., medical imagery, food, ego-centric views) and long-tail concepts mined from a massive ontology. The engine actively sought out images where the current model performed poorly, creating a curriculum of difficult data.

Phase 4 extended this rigorous process to video. Annotating video is notoriously difficult due to motion blur and occlusion. The engine addressed this by focusing human attention on challenging track scenario videos with crowded scenes or frequent object disappearances which resulted in a rich dataset of masklets that teach the model how to maintain identity over time.

The Result: The output of this engine is the SA-Co dataset, a monumental collection containing 5.2 million high-quality images with over 50 million verified masks. Beyond this, the automated pipeline generated a synthetic dataset of 39 million images and 1.4 billion masks.

Benchmarking Results

Traditional metrics like Average Precision (AP) are valuable but insufficient because they fail to account for calibration on how confident the model is when an object is not there. To address this, the paper introduces a composite metric called cgF1(Classification-Gated F1).

This metric is the product of two distinct scores: pmF1, which measures the geometric precision of the masks on positive examples (pixels), and IL_MCC(Image-Level Matthews Correlation Coefficient), which measures the model’s ability to correctly classify the presence or absence of a concept in the entire image. This effectively penalizes phantom detections, ensuring the model is reliable enough for real-world deployment.

Image PCS

Performance In zero-shot evaluations, on the challenging LVIS dataset, SAM3 achieves a mask AP of 48.8, significantly outperforming the previous best of 38.5. SAM-3 achieves a cgF1 score of 37.2 on the Sa-Co dataset which is more than double the performance of strong baselines like OWLv2.

Video PCS and Tracking Consistency

On public benchmarks like BURST and YTVIS, as well as the new SA-Co/VEval dataset, the model consistently achieves higher scores in tracking consistency metrics (pHOTA). The architectural decision to tightly couple the detector with the tracker pays off here.

Key Takeaways from SAM-3 model

If you are planning to use SAM-3 in your pipelines, here are the key operational takeaways:

- Start with Text, Refine with Boxes: The workflow is designed to start with a noun phrase. If the model misses a specific type of object, add a single positive box exemplar. This usually fixes the concept understanding immediately.

- Trust the Presence Score: If you are building an application for counting objects or filtering images, use the presence output. It is highly calibrated and helps avoid processing images where the object doesn’t exist.

- Use for Video Analytics: The re-prompting mechanism makes SAM-3 much more stable than pure tracking models. It effectively resets itself when an object comes out from behind an obstruction.

- Ambiguity Handling: Concepts can be vague (e.g., “bat” could be an animal or sports gear). SAM-3 has an ambiguity module trained to handle these cases. Design your user interface to allow users to guide the model if the first output isn’t the specific interpretation intended.

Final thoughts

SAM-3 is a major step forward because it unifies detection, segmentation and multi-object tracking. By moving from pixels to concepts, and backing it up with a presence-aware architecture and a massive data engine, it provides a robust solution for open-vocabulary tasks in both static images and complex videos.

References

SAM-2 focuses on Promptable Visual Segmentation (PVS), where you must click on or select a specific object to segment it. SAM-3 introduces Promptable Concept Segmentation (PCS). This means you can provide a text description (e.g., “red car”) or a visual example, and the model will automatically find, segment, and track all instances of that concept across the image or video.

Yes. SAM-3 is a unified model. While its major new feature is text-to-segmentation, it fully supports the workflow of previous versions. You can start with a text prompt to find all objects, and then use clicks or box prompts to interactively refine the masks or correct specific errors, just like in SAM-1 and SAM-2.

OpenCV reads images in BGR format by default, but the SAM-3 model(and the PIL library) expects input in RGB format. If you skip this conversion step, the model will misinterpret color-based features, for example, it might see a “red apple” as blue.

Yes. In the provided script, the TEXT PROMPT variable can accept a list of concepts separated by commas(e.g., `”dog, cat, frisbee”`). The Sam3Processor encodes this single string and the model performs multi-label detection in a single pass, returning masks for all recognized concepts found in the current frame.

The output[“masks”] returned by the processor are standard binary tensors. While the provided script uses them for visual overlays, you can use these raw arrays for downstream logic such as calculating the area to estimate object size, using them as alpha channels for background removal, or creating collision boundaries for game physics.

100K+ Learners

Join Free OpenCV Bootcamp3 Hours of Learning