For over a decade, progress in deep learning has been framed as a story of better architectures. Yet beneath this architectural narrative lies a deeper and often overlooked question – how do models actually learn over time? This question lies at the heart of Nested Learning, a new paradigm that reframes modern AI systems not as static networks trained once, but as systems of nested learning processes.

Convolutions replaced handcrafted features. Residual connections enabled depth. Attention replaced recurrence. Transformers replaced almost everything.

Despite these breakthroughs, several fundamental problems remain unresolved:

- Models struggle with continual learning

- Learning effectively stops after deployment

- Adaptation through in-context learning is temporary

- Intelligence appears brittle rather than cumulative

These limitations suggest that architectural innovation alone may not explain modern model behavior.

Nested Learning challenges the dominant assumption that intelligence emerges primarily from architectural depth. Instead, it argues that intelligence arises from how learning itself is organized – across multiple levels, time scales, and memory systems. From this perspective, many successes attributed to deep architectures are better understood as the result of learning-within-learning, hidden inside optimization, memory updates, and inference-time adaptation.

This shift in perspective forces us to ask a more fundamental question: What if architecture is not where intelligence originates?

Nested Learning proposes a radical – but surprisingly consistent – answer: The trustworthy source of intelligence lies in how learning itself is structured, not in how layers are stacked.

The Limits of Architectural Thinking

For much of modern AI research, progress has been explained almost entirely through the lens of architecture. When models improved, the explanation was usually straightforward: a new layer type was introduced, a better block was designed, or a deeper network became trainable. This architectural focus shaped how we think about intelligence in machines.

In this view, a model is essentially a static structure – a carefully designed arrangement of layers and connections. Learning is treated as occurring outside this structure, during a separate training phase, after which the model is considered complete.

This way of thinking leads to an implicit separation:

- Architecture is responsible for representation and reasoning

- Optimization is merely a tool used to adjust weights

- Learning happens only during training

- Inference is a fixed computation with no learning involved

This separation appears natural because it aligns with how most deep learning systems are built and deployed. However, it also hides several significant limitations.

When Architecture Becomes the Only Explanation

If architecture alone were the key driver of intelligence, we would expect more profound and more expressive models to naturally exhibit robust continual learning, stable long-term memory, the ability to improve after deployment, and graceful adaptation without forgetting.

In practice, this does not happen. Even the most advanced models:

- forget previously learned information when fine-tuned

- cannot retain new knowledge gained during inference

- rely on external systems for memory and adaptation

- behave as if learning stops once training ends

These failures are not due to a lack of representational power. They arise because learning itself is constrained by its organization, not by the architecture’s expressiveness.

The Hidden Assumption Behind Deep Architectures

Architectural thinking assumes that stacking layers automatically increases intelligence. But this assumption quietly ignores an important question:

What is actually changing as information flows through these layers?

Most architectural components, regardless of their sophistication, do not change during inference. They process information, but they do not learn from it. The model may appear adaptive through mechanisms like attention or in-context learning, but these adaptations are temporary and leave no lasting trace.

This creates an illusion of intelligence:

- the model responds flexibly

- behavior changes with context

- outputs appear task-aware

Yet nothing is truly learned or remembered beyond the current input window.

Why does this become a Problem in Continual Learning?

The limitations of architectural thinking become especially clear in continual and lifelong learning scenarios. Human learning is cumulative – we do not reset after each experience. Our learning systems update continuously, at different speeds, and across different memory layers.

Most deep learning architectures, however:

- have a single learning phase

- rely on a single optimization loop

- freeze all parameters at inference time

Regardless of how complex the architecture is, this design fundamentally prevents genuine continuous learning.

What Is Nested Learning? (Intuition First)

At its simplest, Nested Learning is the idea that learning itself can be layered.

Traditional machine learning treats learning as a single process: data flows through a model, errors are computed, and parameters are updated. Once training is complete, this learning process stops. The model is then deployed as a fixed system that can only process inputs, not learn from them.

Nested Learning challenges this assumption by asking a deeper question:

What if a model is not a single learner, but a system made up of multiple learners learning at different speeds?

From One Learner to Many Learners

To understand Nested Learning intuitively, imagine learning as a hierarchy rather than a single loop.

Instead of this familiar picture:

Input → Model → Loss → Update Parameters

Nested Learning proposes something more layered:

Fast learner (adapts immediately)

↓

Slower learner (consolidates patterns)

↓

Even slower learner (shapes how learning happens)

Each level learns from experience, has its own memory, updates at its own pace, and influences the levels below it. In other words, learning happens inside learning.

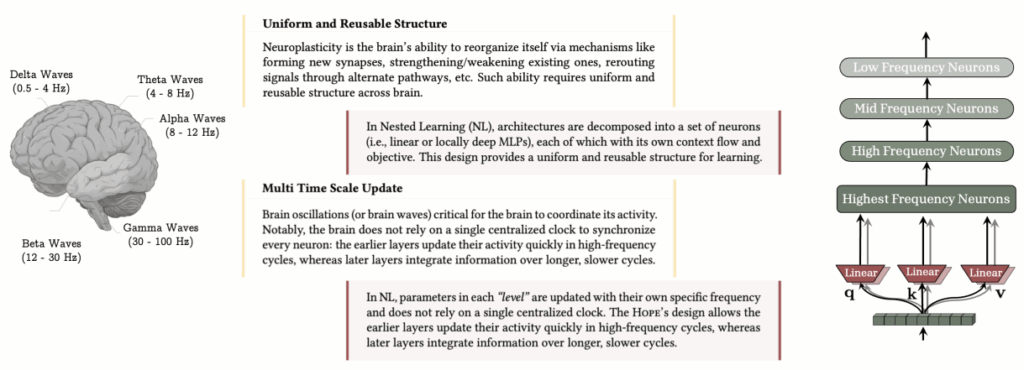

Learning at Different Speeds

A crucial idea in Nested Learning is update frequency. Not everything in a learning system should change at the same rate.

For example:

- Some components may adapt every time a new input arrives.

- Others may update only after many experiences.

- Some may change so slowly that they appear almost fixed.

Nested Learning explicitly models this by allowing fast updates (short-term adaptation), medium-speed updates (pattern consolidation), and then slow updates (long-term structure and learning rules).

This introduces a new notion of depth – depth in time, not just depth in layers.

Why This Is Different from “Just Deep Learning”

It is important to clarify what Nested Learning is not.

Nested Learning is not:

- simply stacking more layers,

- adding more parameters,

- or making networks deeper or wider.

Those approaches increase representational capacity, but they do not change how learning itself works. Nested Learning, by contrast, changes the organization of learning:

- learning is no longer confined to a single training phase,

- learning can continue during inference,

- learning rules themselves can be learned or adapted.

This is why Nested Learning can naturally explain phenomena such as:

- in-context learning,

- fast adaptation without parameter updates,

- optimizer-dependent behavior,

- and the illusion of intelligence in large models.

Why This Matters?

Once learning is viewed as a nested system rather than a single loop, many puzzling aspects of modern AI start to make sense:

- Why optimizers matter so much

- Why attention enables temporary learning

- Why models feel adaptive but forget immediately

- Why continual learning remains difficult

Nested Learning does not add complexity for its own sake. Instead, it provides a clear, unified way to describe how modern learning systems actually behave, rather than how we traditionally draw them.

This intuition sets the stage for the remainder of the discussion, in which we will examine how memory, optimization, attention, and architectures fit naturally into this nested view of learning.

Associative Memory: The Foundation of Nested Learning

At the heart of Nested Learning lies a simple but powerful idea: learning is fundamentally a memory process.

Humans learn by forming associations between experiences, outcomes, actions, and contexts. This ability to connect events and retrieve those connections later is known as associative memory, and it is a core mechanism in human cognition.

Nested Learning argues that modern machine learning systems operate in a similar manner. Whether we look at neural networks, optimizers, attention mechanisms, or fast-weight models, they all function as systems that store and retrieve associations. The difference lies not in whether they store memory, but in:

- what they store,

- how long they store it,

- and how it influences future behavior.

A crucial distinction is made here:

Memory is a neural update caused by an input, while learning is the process of acquiring effective and useful memory.

This framing allows Nested Learning to unify concepts that are usually treated separately, such as memorization, generalization, optimization, and adaptation.

Learning as Memory Compression

From the Nested Learning perspective, training a model is not merely minimizing loss; it is compressing experience into memory.

When a model encounters data, it produces predictions. Any mismatch between prediction and reality generates a signal that indicates surprise. Over time, these surprise signals are compressed into the model’s internal state, shaping how it responds to future inputs.

Seen this way:

- Training is a memory acquisition process

- Parameters are compressed representations of past experience

- Generalization emerges from how memory is compressed, not from storing everything verbatim

This view explains why models can generalize, forget, or overfit—not as architectural quirks, but as consequences of memory compression strategies.

Optimizers as Memory Systems

Nested Learning makes a bold but illuminating claim: optimizers are not just training tools—they are learning systems themselves.

Traditional descriptions treat optimizers like SGD, momentum, or Adam as external algorithms applied to a model. Nested Learning instead views them as associative memory modules that:

- observe gradients (signals of surprise),

- compress these signals over time,

- and influence how the model’s parameters evolve.

Different optimizers store different kinds of memory:

- Some remember recent gradients

- Some track long-term statistics

- Some balance stability and adaptability

This is why changing the optimizer – without changing architecture – can dramatically alter a model’s behavior. From the Nested Learning viewpoint, this is expected: you are changing the learning system itself.

Nested Optimization: Learning Happens at Multiple Levels

One of the central insights of Nested Learning is that learning does not happen at a single level.

Instead, a machine learning system can be decomposed into multiple optimization processes, each operating at its own pace. Some components update rapidly, reacting to immediate inputs. Others update slowly, providing stability and long-term structure.

These optimization processes are:

- interconnected but not identical,

- operating simultaneously,

- ordered by how frequently they update.

This leads to a new understanding of model complexity. Depth is no longer measured by the number of layers, but by the number of learning processes embedded within the system.

Update Frequency: A New Organizing Principle

To formalize this idea, Nested Learning introduces update frequency as a key organizing concept.

Every component in a learning system – whether it is a weight matrix, a memory state, or an optimizer variable – can be characterized by how often it updates.

- Fast-updating components handle immediate adaptation

- Medium-speed components consolidate patterns

- Slow-updating components encode long-term structure

By ordering components based on update frequency, Nested Learning provides a principled way to describe learning hierarchies without relying on rigid architectural distinctions.

Knowledge Transfer Between Learning Levels

Having multiple learning levels raises an important question: how does knowledge move between them?

Nested Learning identifies several ways in which information can flow across levels, without requiring everything to be trained end-to-end.

Parametric Knowledge Transfer

In this form, knowledge is transferred through parameters. Slower-learning components shape the behavior of faster ones by defining how they operate or initialize. This is common in systems where long-term knowledge guides short-term adaptation.

Non-Parametric Knowledge Transfer

Here, knowledge flows through inputs, outputs, or context rather than shared parameters. Attention mechanisms in Transformers are a classic example – each layer conditions the next through its outputs, without directly modifying its internal state.

Gradient-Based Knowledge Transfer

This is the familiar backpropagation-based learning where multiple components share a gradient signal but update at different rates. Nested Learning treats this as one possible form of interaction, not the default or the only option.

Learning via Initialization: Meta-Learning Revisited

Nested Learning provides a natural interpretation of meta-learning approaches, such as learning good initializations.

From this perspective:

- A higher-level learning process does not solve tasks directly

- Instead, it learns how lower-level learning should begin

This explains why techniques like meta-learning can enable rapid adaptation: they transfer knowledge through starting conditions rather than explicit rules.

Learning via Generation: Weights and Context

Another powerful form of knowledge transfer occurs when one learning process generates something for another.

This can take two forms:

- generating parameters (as in hypernetworks),

- or generating learning context (as in learned optimizers or adaptive training pipelines).

In both cases, learning is no longer confined to adjusting weights – it extends to shaping the learning environment itself.

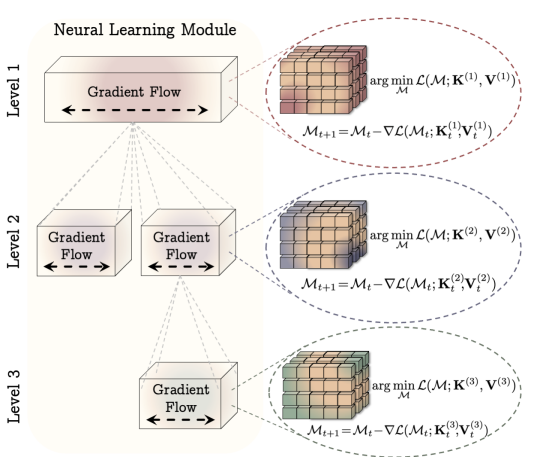

Neural Learning Modules: Unifying Architecture and Optimization

All of these ideas come together in the concept of a Neural Learning Module.

A Neural Learning Module is not just a network block. It includes:

- parameters,

- memory,

- update rules,

- and interactions with other learning modules.

Crucially, architecture and optimization are no longer treated as separate design choices. They are seen as jointly defining the behavior of the learning system.

This perspective becomes especially important in continual learning settings, where there is no clear boundary between training and inference.

Stacking Learning Levels: A New Kind of Depth

Nested Learning introduces a new meaning of depth in machine learning.

Rather than stacking layers to increase representational power, Nested Learning stacks learning levels to increase:

- adaptability,

- memory persistence,

- and temporal reasoning capability.

This kind of depth enables:

- higher-order in-context learning,

- latent computation,

- and gradual knowledge accumulation over time.

Optimizers as Learning Modules

Nested Learning fundamentally changes how we think about optimization. Instead of viewing optimizers as external tools used only during training, Nested Learning treats optimizers themselves as learning systems – systems that store memory, compress experience, and shape long-term behavior.

This section explains why backpropagation, momentum, and modern optimizers are better understood as associative memory modules, and why this perspective is essential for continual learning.

Backpropagation as an Associative Memory

Backpropagation is often described as a mechanical process: compute gradients, update weights, repeat. Nested Learning reframes this process in a more revealing way.

From the associative memory viewpoint, backpropagation:

- observes how surprising a model’s prediction is,

- associates each input with its corresponding error signal,

- and stores this association inside the network’s parameters.

In other words, backpropagation does not merely adjust weights – it memorizes how wrong the model was for different inputs.

Each layer in a network:

- receives a localized error signal,

- treats that signal as feedback about its behavior,

- and updates itself accordingly.

Seen this way, a neural network trained with backpropagation becomes a distributed memory system, where each layer stores associations between inputs and local prediction errors.

Why This Perspective Matters

This interpretation explains several important phenomena:

- Why is training sensitive to data order

- Why models generalize instead of memorizing raw inputs

- Why error signals, not labels, are what truly drive learning

Backpropagation becomes a compression process, where large volumes of experience are distilled into a compact internal memory.

Momentum-Based Optimizers as Associative Memories

Momentum-based optimizers introduce an additional layer of learning.

Instead of updating weights directly from the latest gradient, momentum:

- accumulates gradient information over time,

- smooths short-term fluctuations,

- and remembers consistent directions of improvement.

From the Nested Learning perspective, momentum is not just acceleration. It is a separate memory module that learns how gradients evolve.

This creates a nested structure:

- the inner learning process stores gradient history,

- the outer learning process updates the model’s parameters using this stored memory.

As a result, learning itself becomes multi-level.

Why Momentum Changes Learning Behavior

This explains why momentum-based optimizers:

- converge more reliably,

- resist noisy gradients,

- behave differently from plain gradient descent.

They do not simply move faster – they remember better.

Optimizers as Nested Learning Systems

Modern optimizers such as Adam, RMSProp, and related variants extend this idea further.

These optimizers:

- maintain multiple internal memory states,

- track statistics of past gradients,

- adapt learning behavior over time.

From the Nested Learning viewpoint:

- each internal state is a learning process,

- each learning process operates at a different frequency,

- together they form a nested system of associative memories.

This is why changing an optimizer – without changing the architecture – can dramatically alter:

- convergence behavior,

- stability,

- generalization,

- and forgetting patterns.

Long-Context Understanding in Optimizers

Most optimizers are designed with short memory.

They emphasize recent gradients while rapidly discounting older information. This design works well for static training scenarios but breaks down in continual learning.

Nested Learning highlights a key limitation:

- standard momentum acts like a low-pass filter,

- it gradually forgets earlier gradients,

- and cannot recall the long-term optimization history.

This means that in continual learning:

- optimizers may push parameters in directions that harm previously learned tasks,

- not because the model lacks capacity,

- but because the optimizer lacks long-term memory.

Why This Is a Memory Problem, Not a Model Problem

Catastrophic forgetting is often blamed on architectures. Nested Learning shows that forgetting can originate inside the optimizer itself.

If the optimizer cannot remember past gradient structure, it cannot protect previously learned knowledge.

Designing More Expressive Optimizers

To address this limitation, Nested Learning proposes treating momentum as a general associative memory, rather than a simple accumulator.

This opens the door to more expressive designs:

- momentum with richer internal representations,

- memory systems that selectively forget or retain gradients,

- optimizers that adapt their own memory capacity.

Rather than storing a single compressed summary of past gradients, optimizers can:

- learn meaningful mappings between gradients and updates,

- retain information over longer time horizons,

- and support continual learning more naturally.

Optimizers Beyond Gradient Descent and Momentum

Nested Learning also challenges the idea that gradient descent is the final word in optimization.

By reinterpreting backpropagation as a self-referential learning process, Nested Learning shows that:

- updates can depend on internally generated signals,

- learning rules themselves can evolve,

- and optimization can become context-aware.

This leads to a broader class of learning rules where:

- the model helps generate its own learning signals,

- memory is actively managed,

- and learning continues beyond the traditional training phase.

Optimizers in Continual Learning Settings

In continual learning, optimizers play a far more critical role than is usually acknowledged.

Nested Learning highlights an important asymmetry:

- model parameters may be frozen or reset,

- but optimizer states often contain valuable knowledge about the learning process.

Preserving and managing optimizer memory:

- can improve stability,

- reduce forgetting,

- and enable smoother adaptation over time.

This insight suggests that optimizers should be treated as first-class components of learning systems, not disposable training utilities.

Key Takeaway: Optimization Is Learning

The central message of this section is clear:

Optimization is not something that happens to a model.

Optimization is something the model does.

Backpropagation, momentum, and modern optimizers are all instances of learning systems nested inside larger learning systems.

Understanding optimizers as associative memories:

- unifies architecture and optimization,

- explains optimizer-dependent behavior,

- and provides a principled foundation for continual learning.

Existing Architectures as Neural Learning Modules

One of the most powerful claims of Nested Learning is that modern neural architectures are already nested learning systems, even though we rarely describe them that way. Transformers, recurrent models, and their many variants differ less in structure than in how learning, memory, and update rules are organized across levels.

In this section, we reinterpret popular architectures as Neural Learning Modules – systems in which learning, memory, and optimization are inseparable.

Sequence Models as Associative Memory Systems

Modern sequence models – such as Transformers and recurrent architectures – can be understood as systems that learn mappings from keys to values based on context.

From the Nested Learning viewpoint:

- keys represent what the model attends to,

- values represent what the model retrieves or stores,

- queries determine which memories are activated.

What differs across architectures is not the existence of memory, but:

- whether the memory is parametric or non-parametric,

- whether it is persistent or temporary,

- and at which learning level it operates.

This reframing allows us to view sequence models as instances of nested systems of associative memory, rather than fundamentally different architectural families.

Separating Learning Levels in Sequence Models

A crucial insight from Nested Learning is that not all components of a model learn at the same speed.

In sequence models:

- projection layers (e.g., linear mappings) usually update slowly,

- memory mechanisms (e.g., attention or recurrent states) update rapidly,

- and optimizer states update even more slowly.

For clarity, Nested Learning focuses on the higher-frequency components – the parts of the model that adapt quickly to incoming sequences – while treating slower components as providing structure and stability.

This separation indicates that learning occurs during the forward pass, not only during training.

Softmax Attention as Non-Parametric Associative Memory

From the associative memory perspective, softmax attention can be viewed as a non-parametric memory mechanism.

Rather than learning memory through gradient updates:

- attention retrieves information directly from the current context,

- memory is constructed on the fly from input tokens,

- and no persistent memory is stored beyond the sequence.

This explains why softmax attention excels at short-term reasoning, adapts flexibly to context, but cannot accumulate knowledge over time.

In Nested Learning terms, softmax attention performs high-frequency, non-parametric learning without consolidation.

Key Takeaway: Architecture Is a Shadow of Learning

The central message of this section is simple but profound:

What we call “architecture” is often just the visible outcome of nested learning processes operating at different levels.

To understand, design, and improve learning systems – especially for continual learning – we must stop treating architectures as static objects and start treating them as dynamic systems of learning modules.

Conclusion

Nested Learning invites us to rethink one of the most deeply ingrained assumptions in modern AI: that intelligence primarily emerges from architectural complexity. Throughout this article, we have seen that this assumption, while convenient, is incomplete. Many of the behaviors we attribute to deep architectures – adaptation, reasoning, in-context learning, and even apparent intelligence – are better explained by how learning itself is structured, rather than by how layers are arranged.

This shift in perspective has profound implications. It explains why optimizer choice matters as much as architecture. It clarifies why in-context learning feels powerful yet fleeting. It exposes why continual learning remains difficult despite massive models. Most importantly, it offers a principled path forward – one that focuses not on stacking more layers, but on designing learning systems that operate across multiple time scales, manage memory explicitly, and continue learning beyond deployment.

100K+ Learners

Join Free OpenCV Bootcamp3 Hours of Learning